Many folks are failing to understand CSRF properly, and how to protect against it.

Let’s do this from the beginning and look at what works, and why.

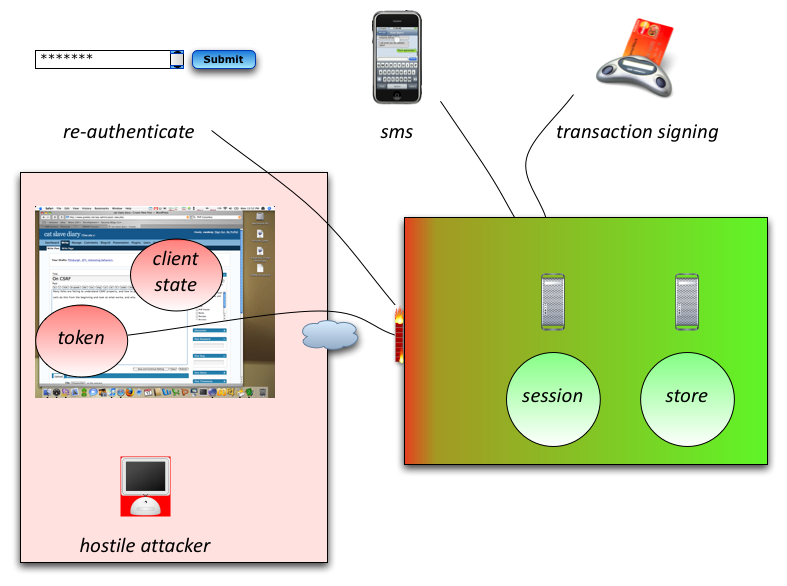

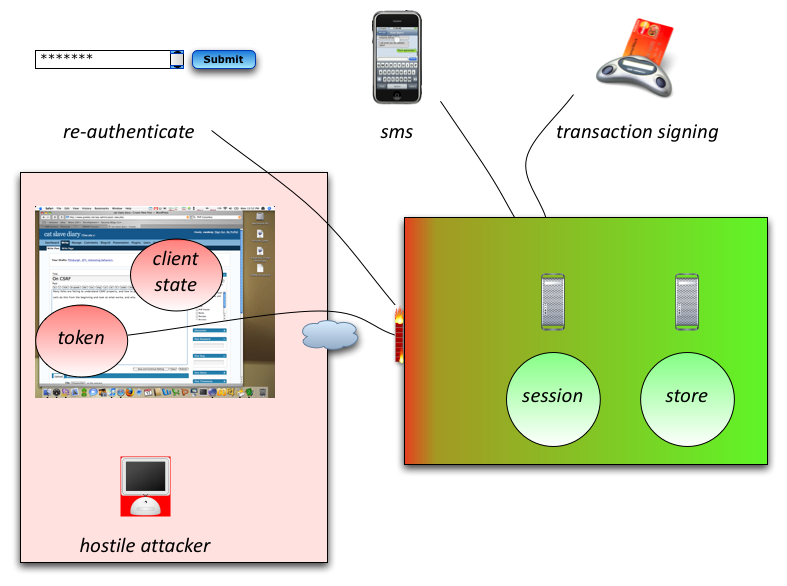

Click for full size version.

Cross-site request forgeries are simple at heart; force the victim to use the victim’s session and credentials to perform authorized work. This almost always uses XSS as the injection path, and can take the form of a hybrid attack, stored or reflected XSS, or a pure DOM attack (including remote script to take over the page).

Typically, a simple CSRF might look like this:

<img src=”logout.php”>

If the application has a logout.php, including a URL will force the victim’s browser to load logout.php. As per normal, the user’s credentials (the session) is sent with the request to logout.php. If logout.php is not CSRF aware, it will log out the user.

This is simple DoS attack. However, imagine if you could do this for Internet Banking, forcing the user to transfer money from their account to a nominated attack account or via a wire transfer service. Unfortunately, this attack is present in every application with a XSS problem, which means > 90% certainty the apps you use have CSRF issues.

What can be done, and what doesn’t work and why

The first thing to realize is to look at the diagram above. Anything in the red box is 0wned by the attacker if they have access to run their script on your user’s browsers. This includes:

a) session (with its implied credentials)

b) credentials (if any, such as Basic auth or NTLM auth)

c) random tokens

d) the entire DOM (i.e. all aspects of the page’s look n feel, as well as how it interacts with your server).

Now there are some good ideas to prevent what I call “no click” attacks. These are like the example above – just by viewing a page, the attacker forces the victim to perform their actions. In order of usefulness:

Move from GET to POST

This is in the HTTP RFC – any request that *alters* the state of the application (such as transferring money, logging folks out, etc), SHOULD be done via verbs other than GET. In our case, we choose to use POST as it’s simple. This raises the bar … a little. Anyone who can code basic JavaScript can get around this.

Add a random token to the request

This scheme is simple: add a nonce hidden field to the form, and check that the nonce is the same on the server upon return. You know what? This will defeat all no click attacks, but will not block advanced hybrid attacks, like the Samy worm.

This approach is done by most anti-CSRF tools out there today, including the CSRF Guard from OWASP. It works… against script kiddies.

Add the session ID to the request

On the surface, this is even simpler than the previous example, and attempts to provide check that the session identifier is sent with the request, thus preventing simple e-mail attacks. However, this misses the point – the victim’s browser sends the request, thus including the credentials. So this is a false mechanism – you’re just repeating what the web server does to associate you with your session, and therefore, this mechanism is not a valid or viable method of protecting against CSRF.

Ask the user for a confirmation that they want to do the action

Many CSRF attacks send one request and will fail if there is a second page asking for confirmation. Guess what – this does not prevent scripted CSRF. Samy worm broke new ground in many different ways – it did a multi-page submit process to make a million folks their hero. But this approach is nearing the correct solution.

Ask the user for their password

In this scenario, the attacker should not know the user’s password, so we’re moving towards the correct solution for CSRF as it’s out of band thus not knowable in an automated way.

However, anyone who has been phished or knows what phishing does will realize straight away why this does not work – not only has the attacker full control of the DOM, they can re-write the page any way they wish, including intercepting forms by changing the submit function, intercepting data sent to the server, and they can pop up their own dialog to authenticate their request. Something along the lines of “I’m sorry, your password didn’t work. Please try again”.

SMS authentication

In this scenario, for our high value transactions, you may wish to consider using SMS based two factor authentication. What happens is that the user will get a random code with explanatory text, like this:

“The code is WHYX43 to authorize transferring $2000 to account 23214343 (“My checking account”). If you did not initiate this transfer, please call 1-888-EXAMPLE.”

This takes the app out of the left hand red box to a second red box. Sure, you don’t control this new red box, but to attack this scenario, the attacker must:

a) Attack the application successfully and run their script

b) Be available when the user logs on to the application

c) Attack the telco’s SMS infrastructure such as to intercept the token to re-write the message or redirect the token at the right time

d) Ensure the user cannot reverse the transaction because they would most likely receive the SMS or if they didn’t they would be expecting to get a new code which may invalidate the attack token.

This confluence of attacks is not easy. It requires too much, and I personally believe for its cost, this solution cannot be beaten. It doesn’t make it impossible, just really really hard.

Two factor transaction signing

Bring on the big boys. This is how two factor authentication should have been done: authenticate the transaction / value, not the user.

In this scenario, the attacker would have to convince the user to type in a sequence of steps, most likely including the value of the transaction and return a code to the attacker. Phishers are clever, but not clever enough in this case.

I really think that for the highest value systems, two factor transaction signing is the way to go.

Sequencing

This is a counter-measure that I discovered by accident when reviewing a Spring Web Flow app a little while ago. By mixing up SWF’s flow mechanism, we can create really hard to obviate applications.

The approach is this:

Application has a range of functions on a page which perform actions. Each action has a special flow ID, flow step, and random nonce mixed in and calculable from the the server only.

So if you want to create a link to go somewhere, you do it like this:

myUrl = createURL(FLOWID, FLOWSTEP, someRandomFn());

or

myUrl = createFormAction(FLOWID, FLOWSTEP, someRandomFn());

It would create a special link, or a post action. When a user views a page, only those links or form actions are permissable. Therefore, a hostile attacker wishing to go from page x to a goal function g’ simply can’t without that goal function being reachable by x. This means that by introducing the concept of landing pages and confirmation pages for special functions like logout or change profile, you can only do so whilst in the midst of that flow.

Attackers would have to inspect the current URLs to determine where they are and this is not easy if the location is somewhat randomized or commonalized (typical of MVC apps, which have a single entry point).

This could be taken to the next level, forcing the client to perform public key crypto to calculate the correct response token by signing where they want to go like this:

rsToken = sign(serverPublicKey, destination Flow ID, Flow Step);

The server could then determine if the response was calculated by one of its clients, rather than one of the hordes of attack zombies. If the server then eliminated all previous steps as a potential flow source, it would immediately block out the user, or the attacker, and thus make the attack detectable.

This makes it much harder for a hostile DOM / attacker to move you directly to their goal function g’ and thus make the attack delayed, diminished, or at worst detectable. As most attackers are only out for a good time, this may be enough for them to move on to another application which is easier to attack.

However, as it requires re-jigging all applications, and we can’t eliminate XSS in the current set of applications today, I doubt this approach will work outside those who are prepared to try.

Administrative attacks

One of the things that has got my goat up for a while now is why application authors insist on mixing up user and admin privileges in one application. CSRF just makes a very silly non-compliance issue a really stupid and foolish mistake.

Administrators by their very nature use the app a lot more than most users. They have more privileges than your average bear. Attackers using CSRF would be silly not to attack the administrative users of the application.

So… what does this mean?

SOX (I’ll get to this), COBIT, ISO 17799 and a host of other compliance regimes all mandate that users are not administrators. Make it so. Get the administrative functions out of your app today and into their own app. Force the admins to use a different credential. If the admins view user created content, they are still at some risk of CSRF attack, so make sure those pages have the highest levels of anti-XSS and CSRF protection.

SOX is simple and often misused to get unwilling business folks to (at worst) spend big on IT’s latest geegaws or (at best) to fund chronically underfunded security budgets. In any case, the basics are this: your app, if it pertains to the financial underpinnings of your business, must have anti-fraud controls. This essentially boils down to initiator / approver model. If one person is allowed to create an order for $100 million, that same person shouldn’t also be allowed to authorize it. In a perfect world, neither of the two roles mentioned so far wouldn’t receive the order. Fraud thrives when one person can do all three things. So if you have users that can create all three roles, then that user MUST NOT be able to use the application, and that user MUST be extremely heavily audited. Such admins are not users … by law. I hate reviewing such cretinous mistakes, so please fix it. This fixes the CSRF issue as the admins are unlikely to CSRF attack themselves.

In the real world

The problem is that most applications are not high value transaction based systems. They’re forums, blogs, social networking sites, book selling sites, auction sites, etc. What about them?

They should be eliminating XSS in their apps as a matter of priority – XSS is the buffer overflow of the web app world. They need to stop using GET immediately. They should be using random tokens.

These simple methods of stops most simple CSRF. Adding additional protection will provide additional protection – but every application is different. If you need more, add more, but always consider usability. Forcing users to use a two factor authentication device for every page view is impractical and foolish. Choose wisely by protecting only your sensitive functions from abuse.